Review Article

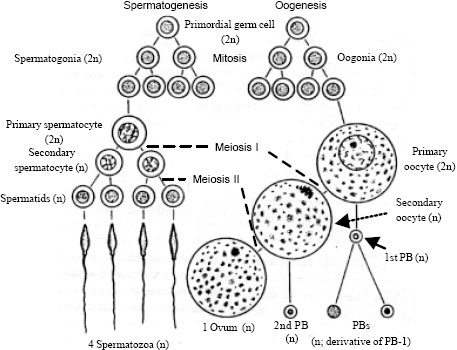

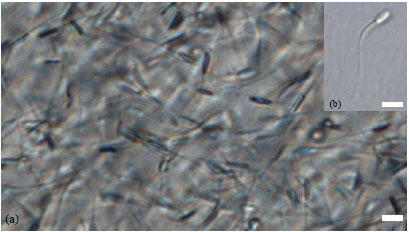

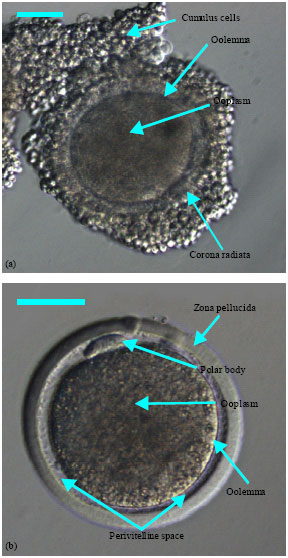

Gametogenesis, Fertilization and Early Embryogenesis in Mammals with Special Reference to Goat: A Review

Animal Biotechnology-Embryo Laboratory (ABEL), Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Malaya, Lembah Pantai, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

R.B. Abdullah

Animal Biotechnology-Embryo Laboratory (ABEL), Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Malaya, Lembah Pantai, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

W.E. Wan-Khadijah

Animal Biotechnology-Embryo Laboratory (ABEL), Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Malaya, Lembah Pantai, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Simoen Dip Reply

This review article appears to be valuable for providing an overview of gametogenesis, fertilization, and early embryogenesis in mammals, with a special focus on goats. This review could be a useful resource for researchers and practitioners working in the field of animal reproduction.

Editor

Thank you for your positive feedback on the review article "Gametogenesis, Fertilization and Early Embryogenesis in Mammals with Special Reference to Goat: A Review." We are glad to hear that the article was useful and informative for you. We hope that this review will contribute to the advancement of knowledge and research in the field of animal reproduction, particularly with respect to goats. Please feel free to share any suggestions or feedback that you may have.