ABSTRACT

Anti-idiotypes (anti-Ids) have a potential role in the immune modulation of various diseases. To study the correlation of anti-Ids with schistosomiasis mansoni morbidity, ELISA using polyclonal idiotypes (Ids) was used to determine the presence of anti-Ids in sera of 69 patients susceptible and resistant to re-infection. Ids were purified against Soluble Worm Antigen (SWAP) from sera of New Zealand white rabbits immunized with SWAP. The results showed that anti-Ids were detected in 15 (40.5%) of susceptible and 21 (65.6%) of resistant patients. Correlation of intensity of infection with age revealed an inverse relationship in patients positive for anti-Ids (regression coefficient β = - 0.47, p<0.05) and contrarily, a direct relationship in patients negative for anti-Ids (β = 0.67, p<0.001). In addition, there was a direct association between the presence of anti-Ids and the lack of schistosome-related symptoms (χ2 = 3.6, p<0.05) and hepatomegaly (χ2 = 9.4, p<0.01). Moreover, comparison of patients positive and negative for anti-Ids revealed that those negative for anti-Ids were more vulnerable to develop symptoms (3.7 times) and hepatomegaly (8.1 times). In conclusion, the study further confirms the role of Id/anti-Id regulatory network as an important participant in the assortment of an improved clinical outcome of schistosomiasis. This may help to formulate a better understanding of the mechanisms of protective immunity in humans and provide perspective for the development of a future vaccine.

PDF Abstract XML References Citation

How to cite this article

DOI: 10.3923/pjbs.2011.375.384

URL: https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=pjbs.2011.375.384

INTRODUCTION

Schistosomiasis causes significant morbidity and mortality in 74 endemic countries with recent studies indicating its burden exceeding official estimates (Moyo and Taonameso, 2005; Nwabueze and Opara, 2007; Bergquist et al., 2008; WHO, 2011). Although chemotherapy is very efficient for elimination of the parasite (Abdel-Aziz et al., 2006; Ali, 2011) but it does not frequently provide resistance against reinfection. Furthermore, with continuing chemotherapy, it seems that drug resistance will appear (Lar and Oyerinde, 2007). However, an age-dependent resistance to reinfection occurs in some patients either naturally or after cure through chemotherapeutic treatment, suggesting that immunity to infection can be acquired and vaccination may be an effective long-term treatment option (McManus and Loukas, 2008; Kouriba et al., 2010).

Several studies have suggested that immune regulation of schistosomiasis would benefit the host by modulating over-vigorous immunopathology, such that most infected individuals do not develop severe disease (De Morais et al., 2002; Montesano et al., 2002). In this study, idiotype/anti-idiotype (Id/anti-Id), regulatory network as suggested by Jerne (1974) may influence the delicate balance between the protective, ineffective, modulating or immunopathogenic mechanisms that determine the totality of the immune response to the parasite (Montesano et al., 1997). Therefore, the study of the correlation of anti-Id responses with the different clinical forms of infection may provide a follow up criterion for morbidity-associated immune responses that may be useful for determining the prognosis of the disease and the evidence of efficacy of possible vaccines (Phillips et al., 1990).

According to Jerne’s network hypothesis, a steady state of immunity is maintained by this interacting network of reciprocal Ids and anti-Ids (Jerne, 1974). Initially, all lymphocytes are in state of immunological dynamic equilibrium mediated by idiotypic interactions. Disturbance of this equilibrium through antigenic challenge may evoke an immune response by expanding Id-expressing clones. Accordingly, these cells may then stimulate anti-Id bearing cells which in turn regulate the initial immune response either by binding to the idiotype on the antibody or T cell receptor (Schick and Kennedy, 1988).

Anti-Ids have been and are being utilized for monitoring and manipulation of several diseases including; viral infections (Hatiuchi et al., 2003; Root-Bernstein, 2005), fungal infections (Magliani et al., 2008), autoimmunity (Ivanova et al., 2008; Tzioufas and Routsias, 2010; Usuki et al., 2010), malignancies (Kawano et al., 2005; Reinsberg, 2007; Magliani et al., 2009) and parasitic infections such as schistosomiasis (Gazzinelli et al., 1988; Phillips et al., 1990; Montesano et al., 1989, 1990).

In a previous study, the existence of anti-Ids was shown to correlate with the resistance against schistosomiasis mansoni reinfection in individuals subjected to chemotherapy programme with praziquantel (Abdeen, 2000). The objective of the current study was to, further investigates the possible role of anti-Ids in shifting the course and outcome of schistosome infection towards the assortment of an improved clinical outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients' materials: The study was performed after obtaining Ethics Committee approval and patients' or their guardian’s written informed consent. Chronic Human Serum (CHS) samples and stool specimens were obtained from 69 (42 males and 27 females) young patients, aged from 10 to 20 years, clinically diagnosed as chronic schistosomiasis mansoni without any concomitant viral hepatitis B, C infections, giardiasis or amoebiasis. Patients lived in 12 country estates around Mansoura, Dakahlia Governorate. They reported at least one treatment with praziquantel four years ago and of course were constantly re-exposed to contaminated water. Of the 69 patients, 32 (46.4%) were presumed resistant to re-infection (without eggs in stool) and 37 (53.6%) were presumed susceptible (with eggs in stool), according to duplicate Kato-Katz thick faecal smears (Kato and Tazaki, 1967). Egg counts were expressed on the basis of Log10 (eggs per gram stool [epg] +1) to include zero counts. However, Normal Human Serum (NHS) samples were collected from 20 age-matched individuals with no history of schistosomiasis or other helminthic infections.

Clinical characteristics of the patients: Patients susceptible to infection including 21 males and 16 females showed various intensities of infection. Hence, they were classified into three grades: severely infected (> 300 epg), moderately infected (100-299 epg) and mildly infected (10-99 epg). They included 26 (70.3%) asymptomatic and 11 (29.7%) suffering minor symptoms of recurrent abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, dysentery and fatigue. On the other hand, resistant patients included 26 (81.3%) asymptomatic and 6 (18.8%) suffering some minor symptoms. Topographic stratification of patients according to age, sex, egg count and clinical characteristics is summarized in Table 1.

Immunized rabbit serum (IRS): IRS was pooled from two male New Zealand white rabbits, aged two months, percutaneously immunized with a total of 2 mg kg-1 body weight of SWAP, divided in three equal doses and administered at monthly intervals. The initial immunization dose was emulsified (1:2 v/v) in Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) (Ausubel, 2002). The second booster immunization (wk 4) was emulsified (1:2 v/v) in Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant (IFA), whereas the third booster immunization (wk 8) was in saline. IRS was collected one month after the last immunization. Normal Rabbit Serum (NRS) was pooled from two matched naive rabbits. All host and parasitic materials were obtained from Biologicals Production Unit (BPU), Theodore Bilharz Research Institute (TBRI), Cairo, Egypt. All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for laboratory animal use (NIH, 1985).

Antigen preparations: Soluble antigens of adult worms (SWAP), cercariae (SCAP) and eggs (SEA) were prepared by homogenization in ice-cooled 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 2 mM Phenylmethyl-Sulfonyl Fluoride (PMSF), pH 7.2 using Teflon glass homogenizer for 30 min (Boctor and Shaheen, 1986).

| Table 1: | Prevalence, intensity of infection [expressed as Log10 (epg+1)] and clinical characteristics of the patients. |

| |

| N: Number of cases, epg: Egg per gm stool. *egg counts were expressed as Log10 (epg+1) to include zero counts. **Hepatomegaly was defined by liver enlargement of more than 2.5 cm below the right costal arch and palpable left lobe. It was confirmed by ultrasonography. + Of the five hepatomegalic susceptible patients, one showed palpable spleen | |

Antigen preparations were clarified by centrifugation at 50000xg for 60 min at 4°C using a Sorvall RC 5 series super speed centrifuge. The supernatant was collected, total protein content was determined by Lowry's method (Lowry et al., 1951) and stored at -70°C until used.

Purification of S. mansoni SWAP-specific rabbit idiotypes (Ids): Twenty milligram of SWAP was conjugated to 2 mL of packed Sepharose-4B (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Upsala, Sweden) as described by the manufacture’s manual. Following the incubation of 2 mL of IRS with the prepared antigen-affinity column, the unbound fraction (IRSunb) was recovered by washing with 0.01 M Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4. The bound fraction containing Ids was eluted with 0.1 M glycine containing 0.15 M NaCl, pH 2.4 and immediately neutralized with 1 M Tris, pH 8. The bound fraction was dialyzed against PBS, lyophilized, reconstituted in deionized distilled water (ddH2O) and kept at -70°C until used.

Preparation of normal rabbit immunoglobulins (NRIgs): Normal rabbit IgG (NRIgG) was purified from NRS using protein G-Sepharose column (Calbiochem). The unbound fraction (NRIgM) containing other Igs, mainly constituted of IgM, was added to an equal volume of 80% saturated ammonium sulfate, mixed over night at 4°C. Next day, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 400xg for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed once with 40% ammonium sulfate and pelted again. The precipitated antibodies were then dissolved in PBS, dialyzed, freeze-dried and reconstituted in ddH2O. Total proteins were measured using Lowry’s method. NRIgG and NRIgM were used separately for characterization of Ids with SDS-PAGE and used in a pool (NRIgs) for preparation of an affinity column for depletion of patients' sera.

Depletion of patients' serum samples: One milliliter of each of pooled NHS (Normal human serum), CHSsusceptible (Chronic human serum of suscepitible patients) and CHSresistant (Chronic human serum of resistant patients) were 1:10 diluted in PBS and repeatedly passed (four times) over NRIgs-affinity column. Compared to the non-depleted serum, the unbound fraction resulted from the last step of purification of each pool was used in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to test its activity against Ids and NRIgG according to the method of Engvall and Perlmann (1971). Conditions of depletion were applied later to individual human serum samples.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE): Ten microgram of each of SWAP, Ids, NRIgG and NRIgM were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE (Laemmli, 1970). The separated protein bands were visualized using silver stain (Oakley et al., 1980). Molecular Weights (MWs) were determined in comparison to low range protein MW standard.

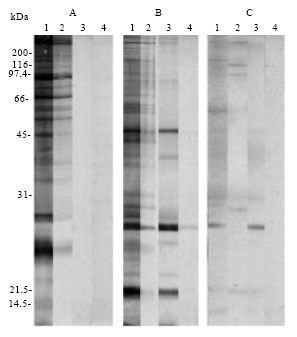

Western blotting analysis: Fifty microgram of each of SWAP, SCAP and SEA were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Nitrocellulose (NC) sheets according to the method of Towbin et al. (1979). Primary antibodies included; 10 μg of Ids and 1:1000 dilutions for each of IRS, IRSunb and NRS. Secondary antibody used was 1:1000 alkaline phosphatase-conjugated polyvalent mouse anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM and IgA). Molecular weights were determined in comparison to broad range protein MW standard.

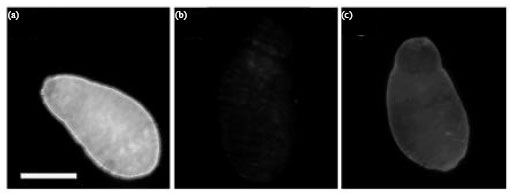

Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IIF): IIF assay was performed on formalin-fixed mechanically transformed 3 h schistosomula according to the method of Gregoire et al. (1987). Mechanical transformation was carried out according to the method of Lazdins et al. (1982). Primary antibodies included 10 μg of Ids and 1:50 diluted IRS and NRS. Secondary antibody used was 1:80 diluted Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. Fluorescence was examined using Leitz fluorescence microscope. Each experiment was repeated three times independently.

Detection of anti-Ids by ELISA: The method of Engvall and Perlmann (1971) was followed with minor modifications. Twenty μg mL-1 of Ids were used for coating ELISA plates. Primary antibodies included 1:100 depleted patients' serum samples. Secondary antibody used was 1:1000 diluted alkaline phosphatase-labeled polyvalent anti-human IgG, IgM and IgA. The plates were monitored using ELISA reader (Lab System Multiskan MCC/340). Each sample was investigated in duplicate and assays were independently repeated three times.

Statistical analysis: All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software. Chi-square test was used to determine the association between anti-Ids and signs of morbidity including schistosome-related symptoms and hepatomegaly. In addition, multiple regression analysis was used to determine the relationship between intensity of infection and age in patients positive and negative for anti-Ids. The significance threshold was set at p-value of 0.05 at 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

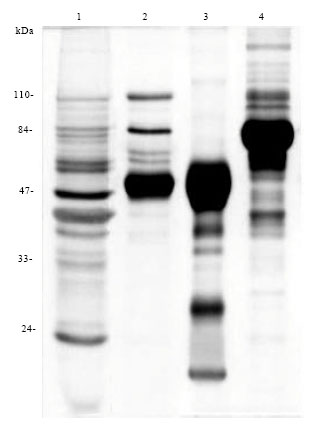

Purity and isotypic constitution of Ids: Ids were subjected to electrophoresis together with SWAP antigen, NRIgG and NRIgM in order to determine its isotypic constitution and exclude the possibility of antigenic contamination during preparation.

| |

| Fig. 1: | Isotypic constitution of Ids in 10% SDS-PAGE, stained with silver stain. Lanes 1-4 are representing (1) S. mansoni SWAP antigen (2) Ids (3) NRIgG and (4) NRIgM |

Comparison of Ids to NRIgG and NRIgM indicated that it is constituted mainly of IgG with some IgM. Furthermore, comparison with SWAP revealed the absence of antigenic contamination (Fig. 1).

Western blotting reactivity of Ids to SWAP, SCAP and SEA: Western blotting was used to determine the immuno-reactivity of Ids to each of S. mansoni SWAP, SCAP and SEA. Ids and IRS showed reactivity to several shared bands between the different antigen preparations, while, IRSunb showed no reactivity to SWAP. Moreover, Ids showed high reactivity against SWAP indicating its successful immunoaffinity purification (Fig. 2). Controls included IRS and NRS.

Surface binding of Ids to S. mansoni 3 h schistosomula: IIF assay was used to determine the reactivity of Ids to the surface of S. mansoni 3 h schistosomula. Ids showed a moderate and uniform surface binding to 3 h schistosomula.

| |

| Fig. 2: | Western blotting analysis of the immuno-reactivity of Ids to antigens of different S. mansoni developmental stages including: (A) SWAP (B) SCAP and (C) SEA. Strips (1) (2) (3) and (4) are corresponding to the primary antibodies IRS, Ids, IRSunb and NRS, respectively |

Image analysis (Pixcavator IA 5.0) of IIF revealed an average fluorescence intensity of 86 for Ids compared to 211 and 15 for IRS and NRS, respectively (Fig. 3). The assay included NRS and IRS as controls.

Removal of the cross-reactive isotypic and allotypic antibodies in human sera: All isotypic and allotypic antibodies present in human sera that can react to rabbit Ids were eliminated by depletion over NRIgs affinity column. As judged by ELISA, four consecutive runs were found enough to ensure the depletion of patients' sera with the retention of anti-Ids activity. This depletion not only purifies the anti-Id fraction of antibodies present in patients' sera but also enhanced its reactivity to Ids. While, the non-specific reactivity was reduced to normal level, anti-Id reactivity of each of CHSSusceptible and CHSResistant recorded O.D405 nm value of 0.56 and 0.67 after depletion compared to 0.46 and 0.6 before depletion, respectively (Fig. 4)

Estimation of anti-Ids and their relationship to age and intensity of infection: Anti-Ids were estimated in serum samples of NHS, CHSsusceptible and CHSresistant. Anti-Ids were detected in 15 (40.5%) and 21 (65.6%) patients susceptible and resistant to infection, respectively. Anti-Ids mean showed significantly higher levels in both CHSsusceptible and CHSresistant compared to NHS (0.44 and 0.55 compared to 0.19, p<0.05, respectively). However, there was no significant difference between mean level of anti-Ids in patients susceptible and resistant to infection (p>0.05, Fig. 5).

| |

| Fig. 3(a-c): | Surface-binding of Ids to formalin-fixed S. mansoni 3 h schistosomula. The assay included (a) IRS (b) NRS and (c) Ids. The bar is representing 50 μm |

| |

| Fig. 4: | Reactivity of pooled NHS, CHSsusceptible and CHSresistant to (a) NRIgG and (b) Ids, before and after depletion over NRIgs |

Multiple regression analysis revealed significant direct relationship between the intensity of infection expressed as Log10 (epg+1) and age (regression coefficient β = 0.67, p<0.001) in patients negative for anti-Ids. In contrary, the intensity of infection showed a significant inverse relationship with age in patients positive for anti-Ids (β = - 0.47, p<0.05; Table 2).

Relationship between the presence of anti-Ids and signs of morbidity: Minor symptoms related to infection were significantly more prevalent among patients negative for anti-Ids compared to those positive for anti-Ids; 13 (39.4%) and 4 (11.1%), respectively. Chi-square test for association indicated a significant direct association between the presence of anti-Ids and lack of symptoms (χ2 = 3.6, p<0.05). The estimated relative risk (R) of symptoms incidence was 3.7 times higher in patients negative for anti-Ids compared to those positive for anti-Ids (Table 2).

On the other hand, hepatomegaly was manifested in 8 (24.2%) out of the 33 patients negative for anti-Ids.

| |

| Fig. 5: | Anti-Ids estimated by ELISA in susceptible and resistant patients. A cut-off value (dashed line) of 0.39 was measured from 20 different NHS samples according to the following equation: Cut-off = anti-Ids mean+3 SD. Anti-Ids were considered positive at O.D≥ cut-off. Anti-Ids mean recorded 0.44 and 0.55 in susceptible and resistant patients, respectively |

| Table 2: | Correlation of intensity of infection [expressed as Log10 (epg+1)] with age in patients positive and negative for anti-Ids as well as the association between anti-Ids in one hand, symptoms and hepatomegaly on the other hand |

| |

| CI: Confidence interval, N: Number of cases, R: The estimated relative risk increase, β: Regression coefficient.*3.7 and 8.1 times increased vulnerability of symptoms and hepatomegaly, respectively, in patients negative for anti-Ids compared to those positive for anti-Ids | |

Interestingly, none of the patients positive for anti-Ids developed hepatomegaly. Chi-square test for association indicated significant direct association between anti-Ids level and the absence of hepatomegaly (χ2 = 9.4, p<0.01). The estimated relative risk (R) of hepatomegalic incidence was 8.1 times greater in patients negative for anti-Ids compared to those with positive anti-Ids (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Human acquired immunity has been hypothesized based on the characteristic age versus infection curves in endemic areas, whereby intensity and prevalence of infection peak in early adolescence and decline in late teenagers and adults (Black et al., 2010). The decline in prevalence rates with age is accompanied with a tendency to accumulate increased levels of IgE antibodies to worm antigens, whereas antibody levels to egg antigens generally decline or remain unchanged (Rouveix et al., 1985; Webster et al., 1997; Naus et al., 2003). Such balanced antibody response may suggest a role for immune regulation in resistance and hence immunopathology of the disease (Pearce and MacDonald, 2002).

One possible explanation for immune regulation is the production of anti-idiotypes against idiotypic determinants on the surface of antigen-specific responding lymphocytes that result in the clearance of selective antibodies and T cell clones and induction of others (Wu et al., 2007; Gilles, 2010). In support of this, experimental schistosomiasis revealed that anti-Ids might take part in the regulation of granulomatous responsiveness around eggs trapped in the hepatic and pulmonary vasculature (Colley et al., 1989; Perrin and Phillips, 1989; Colley, 1990). In humans, there is evidence that Id/anti-Id sensitization to schistosome antigens initiated early in utero in those born to infected mothers (Eloi-Santos et al., 1989).

The current study investigates the possible role of anti-Ids that mimic adult worm antigens to ameliorate the pathological responses of the disease in a cohort of Egyptian patients that have recorded at least one treatment with praziquantel over the last four years. Some of these patients were presumed resistant and others susceptible to reinfection according to the presence or absence of S. mansoni eggs in their stools, in spite of their living under continuous exposure to infection since early childhood.

To ensure the selection of a maximum number of antigenic anti-Ids in patients' sera, polyclonal Ids recognizing a broad range of antigens of schistosome life cycle stages including cercariae, 3 h schistosomula, adult worms and eggs were used (Fig. 2, 3). Ids were mainly constituted of IgG and IgM antibodies (Fig. 1) that recognize a profile of soluble adult worm antigens (SWAP) similar to that recognized with sera of SWAP-immunized rabbits (IRS). This indicates that the activity of Ids was not altered during its purification procedures, while the unbound fraction residues after immunoaffinity purification of Ids (IRSunb) showed no reactivity to SWAP, indicating a successful selection of Ids (Fig. 2).

Anti-Ids were detected in 15 (40.5%) susceptible and 21 (65.6%) resistant patients (Fig. 5) with no significant difference between the two patients' groups (0.44 and 0.55 O.D405nm, respectively, p>0.05). The ability of human anti-Ids to recognize rabbit Ids demonstrated the lack of interspecies barriers (rabbit/human) and the presence of shared idiotypes across species. These findings agree with those previously published for S. mansoni (Al-Khafif et al., 1996) and S. haematobium (Hassan et al., 1999). The mechanism for preserving such Ids across species is unclear. A germ-line gene selection has been suggested (Olds and Kresina, 1990; Moss et al., 1992). Another possible mechanism is that schistosome antigens may act as a super antigen on certain V-regions of the Igs genes on B cell (Tumang et al., 1990).

Assessment of the relationship between patient's age and intensity of infection (expressed as egg counts in the stool), revealed a direct association in patients negative for anti-Ids (regression coefficient β = 0.67, p<0.001) and inverse association in patients positive for anti-Ids (β = - 0.47, p<0.05) (Table 2). This means that at any particular age, patients positive for anti-Ids have a significantly lower egg count than those negative for anti-Ids. Such decline in egg count possibly indicates the development of protective or anti-fecundity immunity. Indeed, egg output is multi-factorial and dependent on other factors including variability in tissue retention and faecal excretion mechanisms (Butterworth et al., 1987; Demeure et al., 1993; Stelma et al., 1994). Moreover, the reduction of worm fecundity whether accompanied with a reduction in worm burden or not, would considerably reduce pathology and affect parasite transmission (Butterworth et al., 1994; Capron et al., 1994). Anyway, the negative relationship between anti-Ids and egg excretion might address the reason for reduction of the pathological responses in patients positive for anti-Ids.

Although the development of morbidity is dependent on the intensity of infection, it might also depend on a number of other factors, both genetic and environmental. These factors might influence the immune responses implicated in the pathological consequences of the disease. For example, a major genetic component has been demonstrated, with susceptibility to severe disease, closely linked to the gene encoding the interferon γ receptor (Dessein et al., 1999). Possible environmental factors include, among others: (1) the maternal infection status, leading to the development of anti-Id T cell responses in the offspring (Eloi-Santos et al., 1989; Novato-Silva et al., 1992) (2) the exacerbating effect of previous exposure to malaria and (3) the co-infection with HIV that might alter the course of schistosomiasis, causing decreased egg excretion and increased egg retention in the tissues (Ouma et al., 2001). In the current study, the possibility of viral or parasitological co-infection was eliminated, leaving schistosomiasis as the major factor for morbidity. Furthermore, the capacity to mount an anti-Id T cell response (Colley et al., 1989) together with the anti-Id antibody response reported herein could contribute to the control of morbidity.

Albeit, chronic schistosomiasis mansoni in humans is a spectral illness and even in endemic foci of relatively high prevalence and intensity of infection, low frequencies of intestinal symptoms are observed by Gryseels et al. (1994) and Davis (1996). Among the investigated subjects, symptoms were about four times prevalent in patients negative for anti-Ids 13 (39.4%) compared to those positive for anti-Ids 4 (11.1%). There was a direct association between the presence of anti-Ids and lack of schistosome-related symptoms (χ2 = 3.6, p<0.05). In addition, the estimated relative risk of symptoms incidence was 3.7 higher in patients negative for anti-Ids. Moreover, evaluation of schistosome-related hepatomegaly showed significant inverse association between the presence of anti-Ids and hepatomegaly (χ2 = 9.4, p<0.01) with patients negative for anti-Ids being 8.1 times more vulnerable to develop hepatomegaly compared to those positive for anti-Ids. Interestingly, hepatomegaly was restricted to patients negative for anti-Ids from both the resistant and susceptible groups (Table 1, 2). Indeed, 34.4% of the presumed resistant subjects were negative for anti-Ids and three of these patients developed hepatomegaly. It is possible that these subjects were mis-assigned to the resistant group due to false negative results of their stool examination. As mentioned earlier a fraction of cases especially those with high tissue retention pass on undetectable low numbers of eggs in stool.

CONCLUSION

The presence of anti-Ids mimicking soluble adult worm antigens is probably an important participant in the induction of protective immune responses which may contribute to the regulation of morbidity and accordingly reduce symptoms and signs of the disease. Such regulation is satisfactory, whether or not accompanied by a reduction in parasite burden as it harbours the desired goal of morbidity control. Moreover, anti-Ids might have the potential to act as prognostic markers for schistosomiasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt. The author thanks all the patients and controls for their participation. Many thanks go to Dr. Ali El-Sherbiny, Mansoura Fever Hospital for kindly providing serum samples, parasitological and clinical data of the patients, Dr. Hanan El Mohamady, Head of Immunology Unit, Naval American Medical Research Unit # 3 (NAMRU-3) and Dr. Abdel Rahman Karawya, Lecturer of Statistics, Mathematics Department, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University for their help.

REFERENCES

- Abdel-Aziz, M.M., A.T. Abbas, K.A. Elbakry, E.A. Toson and M. El-Sherbiny, 2006. Immune response on mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni and treated with myrrh. J. Med. Sci., 6: 858-861.

CrossRefDirect Link - Ali, S.A., 2011. Natural products as therapeutic agents for schistosomiasis. Res. J. Med. Plant, 5: 1-20.

CrossRefDirect Link - Bergquist, R., J. Utzinger and D.P. McManus, 2008. Trick or treat: The role of vaccines in integrated schistosomiasis control. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., 2: e244-e244.

PubMed - Black, C.L., E.M.O. Muok, P.N.M. Mwinzi, J.M. Carter, D.M.S. Karanja, W.E. Secor and D.G. Colley, 2010. Increases in levels of schistosome-specific immunoglobulin E and CD23(+) B cells in a cohort of Kenyan children undergoing repeated treatment and reinfection with Schistosoma mansoni. J. Infect. Dis., 202: 399-405.

CrossRefPubMed - Boctor, F.N. and H.I. Shaheen, 1986. Immunoaffinity fractionation of Schistosoma mansoni worm antigens using human antibodies and its application for serodiagnosis. Immunology, 57: 587-593.

PubMed - Butterworth, A.E., A.J. Curry, D.W. Dunne, A.J. Fulford and G. Kimani et al., 1994. Immunity and morbidity in human schistosomiasis mansoni. Trop. Geogr. Med., 46: 197-208.

PubMed - Butterworth, A.E., R. Bensted-Smith, A. Capron, M. Capron and P.R. Dalton et al., 1987. Immunity in human schistosomiasis mansoni: Prevention by blocking antibodies of the expression of immunity in young children. Parasitology, 94: 281-300.

PubMed - Capron, A., G. Riveau, J.M. Grzych, D. Boulanger, M. Capron and R. Pierce, 1994. Development of a vaccine strategy against human and bovine schistosomiasis background and update. Trop. Geogr. Med., 46: 242-246.

PubMed - De Morais, C.N.L., J.R. de Souza, W.G. de Melo, M.L. Aroucha and A.L.C. Domingues et al., 2002. Studies on the production and regulation of interleukin, IL-13, IL-4 and interferon-gamma in human Schistosomiasis mansoni. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz, 97: 113-114.

PubMed - Dessein, A.J., D. Hillaire, N.E. Elwali, S. Marquet and Q. Mohamed-Ali et al., 1999. Severe hepatic fibrosis in Schistosoma mansoni infection is controlled by a major locus that is closely linked to the interferon-gamma receptor gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 65: 709-721.

PubMed - Eloi-Santos, S.M., E. Novato-Silva, V.M. Maselli, G. Gazzinelli, D.G. Colley and R. Correa-Oliveira, 1989. Idiotypic sensitization in utero of children born to mothers with schistosomiasis or Chagas` disease. J. Clin. Invest., 84: 1028-1031.

PubMed - Engvall, E. and P. Perlmann, 1971. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) quantitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Immunochemistry, 8: 871-874.

CrossRefPubMedDirect Link - Gazzinelli, R.T., J.F. Parra, R. Correa-Oliveira, J.R. Cancado, R.S. Rocha, G. Gazzinelli and D.G. Colley, 1988. Idiotypic/anti-idiotypic interactions in schistosomiasis and Chagas` disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 39: 288-294.

PubMed - Gilles, J.G., 2010. Role of anti-idiotypic antibodies in immune tolerance induction. Haemophilia, 16: 80-83.

CrossRef - Gregoire, R.J., M.H. Shi, D.M. Rekosh and P.T. Loverde, 1987. Protective monoclonal antibodies from mice vaccinated or chronically infected with Schistosoma mansoni that recognize the same antigens. J. Immunol., 139: 3792-3801.

PubMed - Gryseels, B., F.F. Stelma, I. Talla, G.J. van Dam and K. Polman et al., 1994. Epidemiology, immunology and chemotherapy of Schistosoma mansoni infection in a recently exposed community in Senegal. Trop. Geogr. Med., 46: 209-216.

Direct Link - Hatiuchi, K., E. Hifumi, Y. Mitsuda and T. Uda, 2003. Endopeptidase character of monoclonal antibody i41-7 subunits. Immunol. Lett., 86: 249-257.

PubMed - Ivanova, I.P., V.I. Seledtsov, G.V. Seledtsova, S.V. Mamaev, A.V. Potyemkin, D.V. Seledtsov and V.A. Kozlov, 2008. Induction of antiidiotypic immune response with autologous T-cell vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med., 146: 133-138.

PubMed - Jerne, N.K., 1974. Towards a network theory of the immune system. Ann. Immunol., 125: 373-389.

Direct Link - Kato, K. and M. Tazaki, 1967. Schistosomiasis japonica discovered in the large intstine. Shujutsu, 21: 1047-1050.

PubMed - Kouriba, B., B. Traore, D. Diemert, M.A. Thera, A. Dolo, A. Tounkara and O. Doumbo, 2010. Immunity in human schistosomiasis: Hope for a vaccine. Med. Trop., 70: 189-197.

PubMed - Laemmli, U.K., 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227: 680-685.

CrossRefDirect Link - Lar, P.M. and J.P.O. Oyerinde, 2007. A simple process for the experimental induction of resistance in Schistosoma mansoni to antishistosomal agents. Res. J. Parasitol., 2: 63-67.

CrossRefDirect Link - Lowry, O.H., N.J. Rosebrough, A.L. Farr and R.J. Randall, 1951. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem., 193: 265-275.

CrossRefPubMedDirect Link - Magliani, W., S. Conti, L. Giovati, D.L. Maffei and L. Polonelli, 2008. Anti-β-glucan-like immunoprotective candidacidal antiidiotypic antibodies. Front. Biosci., 13: 6920-6937.

PubMed - Magliani, W., S. Conti, R.L.O.R. Cunha, L.R. Travassos and L. Polonelli, 2009. Antibodies as crypts of antiinfective and antitumor peptides. Curr. Med. Chem., 16: 2305-2323.

PubMedDirect Link - McManus, D.P. and A. Loukas, 2008. Current status of vaccines for schistosomiasis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev., 21: 225-242.

PubMed - Montesano, M.A., G.L. Freeman, Jr., G. Gazzinelli and D.G. Colley, 1990. Immune responses during human Schistosoma mansoni. XVII. Recognition by monoclonal anti-idiotypic antibodies of several idiotopes on a monoclonal anti-soluble schistosomal egg antigen antibody and anti-soluble schistosomal egg antigen antibodies from patients with different clinical forms of infection. J. Immunol., 145: 3095-3099.

PubMed - Montesano, M.A., G.L. Jr. Freeman, W.E. Secor and D.G. Colley, 1997. Immunoregulatory idiotypes stimulate T helper 1 cytokine responses in experimental Schistosoma mansoni infections. J. Immunol., 158: 3800-3804.

PubMed - Montesano, M.A., M.S. Lima, R. Correa-Oliveira, G. Gazzinelli and D.G. Colley, 1989. Immune responses during human Schistosomiasis mansoni. XVI. Idiotypic differences in antibody preparations from patients with different clinical forms of infection. J. Immunol., 142: 2501-2506.

PubMed - Moyo, D.Z. and S. Taonameso, 2005. Prevalence and intensity of schistosomiasis in school children in a large sugar irrigation Estates of Zimbabwe. Pak. J. Biol. Sci., 8: 1762-1765.

CrossRefDirect Link - Novato-Silva, E., G. Gazzinelli and D.G. Colley, 1992. Immune responses during human schistosomiasis mansoni. XVIII. Immunologic status of pregnant women and their neonates. Scand. J. Immunol., 35: 429-437.

PubMed - Nwabueze, A.A. and K.N. Opara, 2007. Outbreak of urinary schistosomiasis among school children in riverine communities of Delta State, Nigeria: Impact of road and bridge construction. J. Med. Sci., 7: 572-578.

CrossRefDirect Link - Oakley, B.R., D.R. Kirsch and N.R. Morris, 1980. A simplified ultrasensitive silver stain for detecting proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem., 105: 361-363.

PubMed - Olds, G.R. and T.F. Kresina, 1990. Characterization of a family of monoclonal antibodies which bind Schistosoma japonicum egg antigens and express an interstrain cross-reactive idiotype. Parasite Immunol., 12: 199-211.

PubMed - Pearce, E.J. and A.S. MacDonald, 2002. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol., 2: 499-511.

CrossRefPubMedDirect Link - Perrin, P.J. and S.M. Phillips, 1989. The molecular basis of granuloma formation in schistosomiasis. III. In vivo effects of a T cell-derived suppressor effector factor and IL-2 on granuloma formation. J. Immunol., 143: 649-654.

PubMed - Phillips, S.M., J.J. Lin, N. Galal, G.P. Linette, D.J. Walker and P.J. Perrin, 1990. The regulation of resistance to Schistosoma mansoni by auto-anti-idiotypic immunity. III. An analysis of effects on epitopic recognition, idiotypic expression, and anti-idiotypic reactivity at the clonal level. J. Immunol., 145: 2272-2280.

PubMed - Reinsberg, J., 2007. Detection of human antibodies generated against therapeutic antibodies used in tumor therapy. Methods Mol. Biol., 378: 195-204.

PubMed - Rouveix, B., F. Derouin and M. Levacher, 1985. Evaluation of cellular immune response during chronic schistosomiasis in humans by the leukocyte aggregation test and the leukocyte migration inhibition test. J. Clin. Microbiol., 21: 649-651.

ASCI - Schick, M.R. and R.C. Kennedy, 1988. Anti-idiotype antibodies and immunization against infectious diseases. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev., 2: 343-357.

CrossRef - Stelma, F.F., I. Talla, P. Verle, M. Niang and B. Gryseels, 1994. Morbidity due to heavy Schistosoma mansoni infections in a recently established focus in Northern Senegal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 50: 575-579.

PubMed - Towbin, H., T. Staehelin and J. Gordon, 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: Procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 76: 4350-4354.

PubMedDirect Link - Tumang, J.R., D.N. Posnett, B.C. Cole, M.K. Crow and S.M. Friedman, 1990. Helper T cell-dependent human B cell differentiation mediated by a mycoplasmal superantigen bridge. J. Exp. Med., 171: 2153-2158.

PubMed - Webster, M., R. Correa-Oliveira, G. Gazzinelli, I.R. Viana, L.A. Fraga, A.M. Silveira and D.W. Dunne, 1997. Factors affecting high and low human IgE responses to schistosome worm antigens in an area of Brazil endemic for Schistosoma mansoni and hookworm. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 57: 487-494.

PubMed - WHO, 2011. Schistosomiasis: Number of people treated in 2009. Weekly Epidemiological Rec., 86: 73-80.

Direct Link - Wu, Y., Y. Zhang, X. Xu, P. Lv and X. Gao, 2007. Anti-idiotypic regulatory responses induced by vaccination with DNA encoding murine TCR Vα5 and Vβ2. Cell. Mol. Immunol., 4: 287-293.

PubMed