Research Article

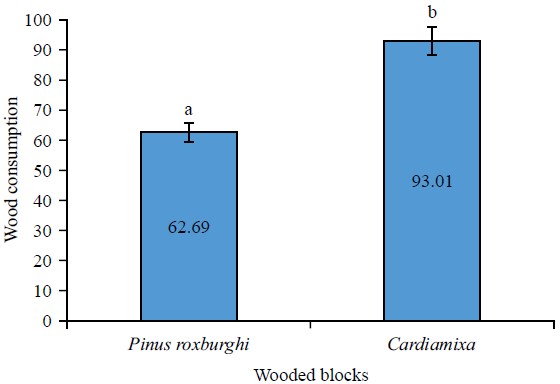

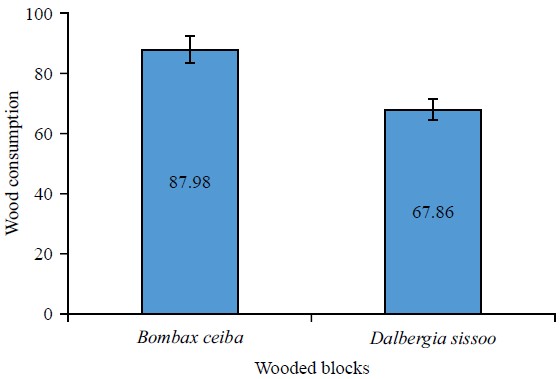

Feeding Preference of Vexatious Microtermes obesi (Wheat Termite) (Blattodea: Termitidae)

University of Lahore, Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Defense Road, Lahore, Pakistan

LiveDNA: 92.32270

Allah Ditta Nadeem

University of Lahore, Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Defense Road, Lahore, Pakistan

Ayesha Aihetasham

Institute of Zoology, Punjab University, New Campus Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan

Sikandar Hayat

University of Lahore, Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Defense Road, Lahore, Pakistan

LiveDNA: 92.35703

ORCID: 0000-0001-9533-086X

Zahid Hussain

University of Lahore, Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Defense Road, Lahore, Pakistan

LiveDNA: 92.26140

Khalid Zamir Rasib Reply

excellent presentation

Editor

Thank you very much for your kind words on our website. It means a lot to SciAlert that you found the presentation excellent. I appreciate your feedback and hope that you continue to find value on our website.