Research Article

Environmental Effects of Nickel-Copper Exploitation on Workers Health Status at Selebi Phikwe Area, Botswana

Department of Geology, Mining and Minerals, University of Limpopo, P/Bag X1106 Sovenga, 0727 South Africa

Exploitation of nickel-copper (Ni-Cu) at Selebi Phikwe, Botswana is considered to have environmental and human health implications. Of particular concern is the labour force, which experiences a higher level of exposure to environmental hazards due to mining, compared to other categories of residents within the Ni-Cu mining environment. Health effects associated with Ni-Cu mining on workers living within the area were thus investigated through the administration of questionnaires. Results depicted workers suffering from different symptoms and illnesses as follows in percentages: body weakness 42, loss of body weight 16, influenza/common colds 66, headaches 70, chest pain 40, repeated coughing 45, need to spit often 6, shortness of breath 18, palpitations 14, regular lower abdominal pain 31, pain when urinating 4, genital discharge at some time 5, nausea/vomiting 12, frequent diarrhoea 12 and constant constipation 10. Values obtained for same symptoms and diseases at the control site were in general lower than those closer to the mining area. Frequent chest pains, repeated coughing, constant influenza/common cold and persistent headaches, which workers of the environment suffer from were very significantly higher compared to those at the control site and incidences of their occurrences increased with closeness to mining area. The unusual high occurrences of these ailments and illnesses coupled with associated diseases among workers at Selebi Phikwe were attributed to several environmental factors including contaminated Particulate Air Matter (PAM) (rich in sulphur and heavy metals) linked to the mining and smelting of Ni-Cu. These findings are in conformity with those of previous related studies and infer possible similarities for workers of business enterprises within other Ni-Cu mining environments around the world.

Most of the production of Ni and Cu are from ore bodies that contain other metals such as gold (Au), cobalt (Co), lead (Pb) and zinc (Zn). In the world, there are more than 30 mines producing Ni-Cu (AME Research, 2006), although there are many others producing Cu and/or Cu with other metals and Ni and/or Ni with its associated metals. Nickel mines are in 22 countries and smelters in 27 countries and there are three times more new Ni projects being developed than those being closed in the world (International Nickel Study Group, 2006). There is more Cu production than Ni and in many more countries (AME Research, 2006). The global demand for these metals has continued to be in the rise and as such their production has also been on the increase, especially in those developing countries such as Botswana whose economy are mineral dependent. The exploitation of Ni-Cu ore, among several other mineral resources such as diamonds, gold, soda ash and industrial minerals in Botswana, has given the country an economic boost (Xavier and Thirtle, 2004). Of particular concern is the exploitation of Ni-Cu ore bodies at Selebi Phikwe, Botswana, which is among the earliest mined ore bodies in the country, having been mined for more than 25 years. In 2005, the exploitation of Ni-Cu in Botswana yielded 68,637 tons of matte (indicating a 27% increase compared to the yield of the previous year) of which 28,212 tons was Ni, 27,704 tons Cu and 326 tons Co (Department of Mines, 2005; Department of Town and Regional Planning, 2006).

The host rock constitutes phlogopite mica-rich amphibolite and the minerals constituting the Selebi Phikwe Ni-Cu orebodies include chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), bunsenite (NiO), chalcocite (CuS), penroseite ((Ni,Cu)Se2) and magnetite (Fe3O4). Cobalt and Cr also occur in most of the minerals (Gallon, 1986; Maier et al., 2008). Chalcopyrite and chalcocite are the main sources of Cu and pentlandite ((Fe,Ni)9S8) is the main source of Ni with bunsenite and penroseite being less dominant (Nkoma and Ekosse, 1999). Pyrrhotite (Fe1-xS) and magnetite are also present in substantive quantities, but are not exploited economically (Nkoma and Ekosse, 1999). The Selebi Phikwe Ni-Cu ore bodies consist of three types of orebodies based on sulphide content and tectonics: massive sulphides, semi sulphides and disseminated sulphides (Gallon, 1986). The massive sulphides are orebodies in which the host rock has been totally replaced by sulphides and consist of pentlandite and pyrrhotite S-bearing minerals. The semi-massive sulphides contain between 40 and 70 wt.% sulphide in a matrix of host amphibolites and garnets are commonly found at the sulphide/amphibolite contacts. The disseminated sulphides are orebodies having 0 to 40 wt.% low-grade sulphide ore with poorly developed mineral zoning (Gallon, 1986).

With a population of 1 500 000 inhabitants, a 3.1% growth rate and a density of 2 persons per km2 (Botswana Government National Census, 1991), Botswana is presently one of the fastest growing economies among the less developed countries of the world and among the top three mineral producers by value in Africa, including South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The economic boom in the country has encouraged the Government to make available incentives such as the Financial Assistance Policy (FAP) for small and large scale businesses and industrial projects (henceforth referred to as business enterprises) which promote economic diversity (Mundi, 2003). The incentives have encouraged investment in commercial, textile, food/hotel, mining, agricultural, service provider and liquor store enterprises in the country and especially in mining towns such as Selebi Phikwe where rapid urbanisation is eminent (Tombale, 2002).

Although big economic gains are being reaped from the mining sector, however, the exploitation of mineral resources could negatively influence the environmental and human health of mining environments in the country. Previous investigations on the biophysical environment of the Selebi Phikwe area by Ekosse (2005a) and Ekosse et al. (2003, 2004) revealed that mining activities have certainly affected the atmosphere, soils, flora and fauna. Mine drainage water and water enriched with leached ions of heavy metals have been known to affect the quality of aquatic organisms and the quality of water received by the downstream communities (Al et al., 1994; Egbu, 2000). Mining activities are reported to have several adverse hydrogeological impacts, including alteration of local surface and sub surface water environments, in terms of both its quality and quantity (Molson et al., 2008; Pérez-López et al., 2007; Robles-Arenas et al., 2006). The Particulate Air Matter (PAM) of mining environments usually contains dust particles rich in heavy metals; particularly of the types being exploited. Studies at Selebi Phikwe revealed its PAM to consist of quartz, pyrrhotite, chalcopyrite, albite and djurleite and concentration levels of heavy metals contained in the PAM related to mineral phases present, which were linked to the orebodies (Ekosse et al., 2004).

Soils around mining environments are contaminated through deposition of PAM, gaseous sorption, tailings dump reactions with meteoric waters and migration and translocation of heavy metals. Soil parameters such as pH, organic matter, particle size, permeability, soil moisture, bulk density and particle density, rate of metal absorption and soil acidity are drastically affected as well as vegetation growth (Aloway and Ayres, 1997). Plants extract metals from polluted soils and mine wastes making them available to animals, including livestock and humans who are higher members of the food chain (Carrillo González and González-Chávez, 2006; Getaneh and Alemayehu, 2006; Luo et al., 2006). Animals including humans living within mining areas are therefore likely to suffer from respiratory problems associated with PAM. Mammals especially sheep and cattle could be more affected than birds, which migrate due to forced changes in climatic conditions. Animal illhealth and calf mortality as a result of geophagia also occur (Elsenbroek and Neser, 2002). Human exposure to PAM rich in heavy metals has been reported to cause inflammatory response in the lungs, which could result in, impaired lung function (Lauwerys et al., 1985; Lucchini et al., 1995; Zayed et al., 1994).

Copper causes irritation to eyes and nose, dermatitis, anaemia, gastric ulcers, renal damage and haemolysis (Flynn et al., 2003; Mielke et al., 2000; Moodie, 2001; Pyatt et al., 2005). Nickel inhalation causes irritation of the nose, sinuses and loss of sense of smell, headache, nausea, vomiting, chest pain and breathing problems and it could also lead to asthma, bronchitis and other respiratory diseases, eventually causing lung cancer (Korre et al., 2007; Nathanail and Smith, 2007). Socio-economic studies conducted within the Selebi Phikwe Ni-Cu mining area suggested the possibility of mining activities having a negative effect on the health of residents there; but the study failed to consider the different categories of residents in order to establish the most affected category. The general health status of residents of the mining area depicted constant influenza/common cold, rampant headaches, persistent chest pains and frequent coughing to be the most dominating health complaints (Ekosse, 2005b; Ekosse et al., 2005, 2006a, b). Studies were also stretched to evaluate the pulmonary health status of its residents, with findings revealing grave health concerns possibly as a result of mining activities (Ekosse et al., 2006b). In spite of the general health complaints of residents, there is the labour force, which is daily more exposed to all the environmental health hazards as a result of Ni-Cu exploitation. Studies conducted by Liu et al. (2005), Ogola et al. (2002) and McGill University (2003) indicated that workers in the highest risk enterprises, such as mining and smelting and those living in mining environments are exposed to a wide range of hazards including contaminated air, which increase their susceptibility to a variety of illnesses and diseases. This particular study therefore aimed at understanding the health effects of workers of business enterprises in the Selebi Phikwe mining and smelting area in Botswana. Their health status was evaluated through a survey and report generated focused on the prevalence of illnesses and diseases affecting the workers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area: Selebi Phikwe area is located in the north-eastern part of Botswana between longitudes 27°47`E and 27°53`E and latitudes 22°55`S and 22° 00`S (Fig. 1). It is approximately 250 km2 and has a population of about 50,000 with a 2.4% constant growth rate since 1991 (Botswana Government National Census, 1991). Rapid population expansion from <5,000 in 1971 to the present population size characterised by 52.5% male and 47.5% female, has led to pressure on existing social and economic infrastructures (Department of Town and Regional Planning, 1996). The male population will probably continue to increase, as it is the dominant gender for mine labour. Twenty six percent of the labour force of over 20,000 (Botswana Government National Census, 1991) is engaged in mining of Ni-Cu. Large scale and small scale industries, commercial businesses and agricultural farms are other economic activities in the Selebi Phikwe environment. Environmental contamination including the release of sulphur rich gases (commonly detected by an obnoxious smell) due to mining activities is eminent at Selebi Phikwe. It is thus suspected that the labour force is exposed to the contaminated atmosphere and do inhale polluted air. The area is therefore nagged with common health problems, which include cardio-respiratory, tuberculosis, common colds/influenza, bronchitis and pneumonia (Botswana Gazette Newspaper, 2000). Aids-related diseases are not as high as in Francistown and Gaborone cities (Botswana Mmegi Newspaper, 2000).

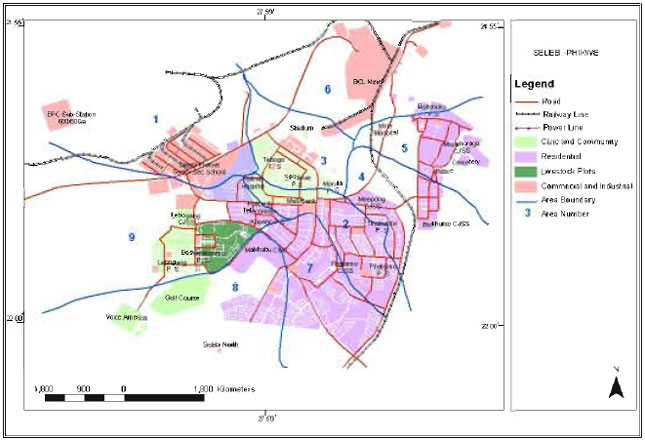

Samples and sampling: The study area was divided into ten sites (Fig. 2, Table 1) based on previous studies by Ekosse et al. (2005) and Ekosse et al. (2003). Two hundred business enterprises participated in this study.

| |

| Fig. 1: | Map of Africa showing Botswana and map of Botswana indicating Selebi Phikwe |

| |

| Fig. 2: | Map of Selebi Phikwe showing the different study sites |

| Table 1: | Location and details of sampling sites within the study area |

| |

This number was chosen after several reconnaissance visits. All the different types of business enterprises at the ten different sites were statistically represented. A non-biased approach was followed, whereby business enterprises were chosen based on their location and type. An equal distribution of questionnaires to all the ten sites was ensured. This approach of an equal number of samples per subpopulations corresponds to the method suggested by Czaja and Blair (1996).

Methods and analytical techniques: This investigation was conducted through the administration of questionnaires and structured interviews. Questionnaires, which covered demographic data, general complaints of workers about personal health and aspects related to death, were administered to business enterprises. Directors of enterprises (who in some cases were the owners) or designated officials (usually managers) responded to the questionnaires. Information concerning the types and locations of the different business enterprises was obtained from the Selebi Phikwe Town Council and Local Government Offices, the Ministry of Trade and Commerce and the Department of Mines, Botswana. This information aided in the physical identification of the business enterprises.

Data was generated in areas related to general complaints about personal health and aspects related to death. Statistical analyses for all the responses obtained from questionnaires were performed using the Statistical Package for Sciences (2003). Cross tabulations were undertaken to establish relationships of study sites to the health status of workers and quantify the research findings.

RESULTS

Business enterprises: The types of business enterprises represented in the study area included 41.2% commercial, 16.6% textile, 21.1% food/hotel, 0.5% mining, 2% agricultural, 9% service providers, 3.5% liquor store types of enterprises while 6% were unspecified. Table 2 gives the details of how the enterprises are distributed according to the study sites. Most of the business enterprises within the study area were established only after the Ni-Cu mine and concentrator/smelter plant became operational. These enterprises are privately owned. The labour force came from neighbouring villages and has remained the source for manpower over the years (Tabelo, 2004). The availability of capital has affected the types of enterprises in the area and with the Government`s FAP, many of the locals are becoming entrepreneurs and general business men (Tabelo, 2004; Valentine, 2000).

General complaints of workers about personal health: Values for >30% were obtained for general body weakness, influenza/common cold, headaches, frequent coughing, constant chest pains and regular lower abdomen pain (Fig. 3).

Health complaints of workers according to study sites: Table 3 gives a more detailed distribution of the various health complaints of the workers in the different business enterprises according to study sites. All the workers in sites four and nine often suffered from constant influenza/common colds and all in sites five and eight often suffered from persistent headaches. In site one, 62% of the workers suffered from body weakness, 90% often had influenza/common colds, 95% regularly suffered from persistent headaches and 90% complained of coughing regularly. Also in the same site, 71% suffered from frequent chest pain and 52% experienced shortness of breath. In site two, 68% of the workers often had constant influenza/common colds and 69% regularly suffered from persistent headaches. In site three, 53% suffered from body weakness. In site four, 82% often suffered from persistent headaches and 55% complained of coughing regularly. In site five, 75% often had influenza/common colds, 50% of repeated coughing and a further 50% suffered from frequent chest pain.

| Table 2: | Types of enterprises according to study sites in the Selebi Phikwe area |

| |

A: Commercial, B: Textile, C: Food/hotel, D: Mining, E: Agricultural, F: Service provider, G: Liquor store and H: Unspecified | |

| |

| Fig. 3: | Percentage distribution of general health complaints of workers of business enterprises in the Selebi Phikwe area, (Legend A = body weakness, B = loss of body weight, C = influenza/common cold, D = headaches, E = coughing, F = unusual spitting, G = chest pain, H = shortness of breath, I = palpitations, J = lower abdomen pain, K = urination with pain, L = genital discharge, M = nausea/vomiting, N = diarrhoea and O = constipation) |

In site seven, 67% of workers often had constant influenza/common colds, 50% suffered from persistent headaches and another 50% complained of repeated coughing. In site eight 57% often had constant influenza/common colds. In site nine, 50% suffered from body weakness, 88% often suffered from persistent headaches and 75% complained of coughing repeatedly whereas another 75% suffered from frequent chest pain. Also in the same site nine, 63% experienced pain in the lower abdomen and 53% complained of persistent headaches and in site 10 53% of the workers also suffered from persistent headaches (Table 3).

Health complaints of workers according to business enterprises: All the workers in the agricultural and mining industries suffered from constant influenza/common colds, persistent headaches and complained of repeated coughing and only all in the agricultural industries complained of frequent chest pain (Table 4).

| Table 3: | Percentage distribution of general complaints of workers about personal health according to study sites in the Selebi Phikwe area |

| |

A: Body weakness, B: Loss of body weight, C: Influenza/common cold, D: Headaches, E: Coughing, F: Unusual spitting, G: Chest pain, H: Shortness of breath, I: Palpitations, J: Lower abdomen pain, K: Urine with pain, L: Genital discharge, M: Nausea/vomiting, N: Diarrhoea and O: Constipation | |

| Table 4: | Percentage distribution of types of general health complaints of workers of different types of enterprises in the Selebi Phikwe area |

| |

A: Body weakness, B: Loss of body weight, C: Influenza/common cold, D: Headaches, E: Coughing, F: Unusual spitting, G: Chest pain, H: Shortness of breath, I: Palpitations, J: Lower abdomen pain, K: Urine with pain, L: Genital discharge, M: Nausea/vomiting, N: Diarrhoea and O: Constipation | |

In the commercial enterprises, 51% suffered from body weakness, 60% often had constant influenza/common colds, 68% often suffered from persistent headaches. In the textile enterprises, 73% often had constant influenza/common colds and another 73% suffered from persistent headaches. In the food/hotel enterprises, 71% often had constant influenza/common colds and 64% suffered from persistent headaches.

In the agricultural enterprises, 75% of the workers had suffered recently from body weakness and 50% often experienced shortness of breath. In the service industries, 50% suffered from recent body weakness, 67% often experienced constant influenza/common colds, 72% suffered from persistent headaches and 56% complained of repeated coughing. Also in the same service enterprise, 50% suffered from frequent chest pain and another 50% had pains in the lower abdomen. In the liquor store enterprise, 57% often had constant influenza/common colds and 86% suffered from persistent headaches. There were a number of enterprises that did not specify the type of activities in which they were involved. In this category, 67% of the workers often experienced constant influenza/common colds and a further 67% had persistent headaches and 58% suffered from repeated coughing (Table 4).

Health complaints based on both type and location of business enterprises: All the commercial, textile and liquor enterprises in site nine, the food/hotel businesses in sites four and seven indicated that <20% of their workers and all the commercial and food/hotel enterprises in sites five and six respectively indicated that 20-30% of their workers both suffered from suffered from general body weakness. Similarly all commercial enterprises in site four and textile enterprises in site one had 40-50% of their workers who complained of unusual general body weakness.

Regarding frequent chest pains, 20% of the commercial enterprises in site one indicated that 81-90% of their workers, 11% of those in site two mentioned that 20-30% of their workers and 100% of those in site four indicated 41-50% of their workers, respectively who suffered from the sickness. In the textile enterprise, 10% of those located in site two had 61-70% of their workers who complained of frequent chest pains. Thirty three percent of the food/hotel enterprises in site one indicated that 81-90% of their workers, 50% of those in site two mentioned that 20-30% of their workers and 100% of those in site three indicated 91-100% of their workers, respectively suffered from frequent chest pains. There were workers at all sites for all the different types of enterprises who suffered from frequent chest pains but respondents could not quantify the percentages.

All the respondents indicated that workers were not sure of whether they had dull chest pains. However, some of the workers complained of moderate chest pains of which all the food/hotel enterprises in site nine found that 31-40% of their workers complained of such. In site nine, all the liquor store enterprises had 71-80% of their workers who complained of moderate chest pains. All the commercial enterprises in site four indicated that 40-50% of their workers complained of regular coughing as well as of experiencing constant chest pains. All the commercial enterprises in site five indicated that 20-30% of their workers had the same symptoms, whereas in site nine, all the commercial enterprises indicated that <20% of their workers complained of coughing regularly as well as experiencing constant chest pains. All the textile enterprises in sites nine and ten had 30-40% and 40-50% of their workers respectively who complained of coughing often as well as of experiencing chest pains.

All the mining enterprises in site four indicated that 20-30% of the workers complained of coughing regularly as well as experiencing frequent chest pains. All the commercial enterprises in site four indicated that 40-50% of their workers complained of repeated coughing as well as of experiencing frequent chest pains. Similarly, all the commercial enterprises in site five indicated that 20-30% of their workers had the same symptoms, whereas in site nine, all the commercial enterprises indicated that <20% of their workers complained of repeated coughing as well and of experiencing constant chest pains. All the textile businesses/industries in sites nine and ten had 30-40% and 40-50% of their workers complaining of repeated coughing as well as of experiencing constant chest pains.

It was only in sites one, two, three and four that workers indicated they often suffered from constipation. In site one, 33% of the commercial enterprises had <20% of their workers and another 33% had 40-50% of the workers who complained of constipation. In site two, 50% of the commercial enterprises and in site three, 100% of similar enterprises had <20% of their workers who suffered from constipation. In The enterprises were however not certain of the type of constipation (dull, moderate and acute) experienced by the workers.

Aspects of death: Figure 4 indicates the reasons for and percentages of, workers admitted to health facilities in the study area. One percent of the enterprises responded that workers were admitted into health facilities because they experienced general body weakness, another 1% because they complained of chest pains and another 1% because of shortness of breath. A further 1% was admitted as a result of pain in the lower abdomen. Furthermore, 1% of the industries responded that workers were admitted into health facilities because of nausea/vomiting, 1% due to diarrhoea, another 1% because of constipation and a further 1% as a result of asthma. 4% of the enterprises responded that workers were admitted into health facilities because of recent unexpected loss of body weight and another 4% of the enterprises indicated that workers were admitted into health facilities because they experienced influenza/common colds. A further 4% were admitted due to AIDS-related diseases, whereas 5% of the enterprises reported that workers were admitted into health facilities because they experienced headaches.

| |

| Fig. 4: | Reasons for and percentage of workers admitted to health facilities in the Selebi Phikwe area |

| |

| Fig. 5: | Causes of death of workers in Selebi Phikwe |

Figure 5 reveals the causes of deaths of workers as depicted from the medical records. 1% of enterprises reported that workers died as a result of malaria, another 1% reported that workers died because of lung disease and a further 1% of the enterprises reported that workers died as a result of meningitis. One percent of the enterprises reported that workers died as a result of stroke. Four percent of the enterprises reported that workers died because of AIDS-related diseases, another 4% reported tuberculosis as the cause of death and a further 4% mentioned having workers who died as a result of pneumonia. There were deceased workers who had passed away from the following diseases: prostrate cancer, cancer of the colon, cardiac arrest, diabetes and heart diseases. The specific cause of deaths of 2% of workers was uncertain but could be attributed to one of the mentioned diseases.

Business enterprises admitted they had cases of death among their workers. Twenty one percent of the respondents of enterprises indicated that deaths did occur in their undertakings. Forty eight percent of the enterprises in site one indicated that deaths of workers did occur in their enterprises. According to study sites, the percentages were as follows: site two, 21%; site three, 13%; site four, 18%; site six, 13%; site seven, 17% and site 10, 20%. None of the enterprises in sites five, eight and nine, however, reported deaths of workers.

In terms of duration of stay of workers prior to death, 1% of the enterprises indicated that these workers had lived in Selebi Phikwe for 11-15 years, another 1% reported that deceased workers had lived in Selebi Phikwe for 16-20 years and another 1% mentioned that deceased workers had stayed in Selebi Phikwe for 21-25 years; yet a further 1% reported having deceased workers who had lived in Selebi Phikwe for 26-30 years. Four percent of the enterprises reported that cases had occurred of workers having died after living in the Selebi Phikwe area for <5 years and 4% reported duration of stay of 6-10 years. Some of the deceased workers lived in Selebi Phikwe for 31-35 years and some others for >36 years. The enterprises reported that most of the workers who had passed away were between 21 and 45 years old. 8% of the enterprises reported that the deaths occurred amongst male workers, while 10% reported that the deaths occurred amongst female workers. Slightly more cases of death were reported of workers who were engaged as smelter/concentrator workers and administrators, teachers, hospital staff, shop/supermarket attendants and housewives than the other categories.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Common ailments, illnesses and diseases reported to be affecting workers of enterprises in the area included high blood pressure, general body weakness, frequent chest pain, repeated coughing, constipation, diarrhoea, constant influenza/common cold, persistent headaches, loss of body weight, lower abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, palpitations, shortness of breath, unusual spitting, genital discharge and cancer. More individuals at the control site suffered from general body weakness, desire to spit often and shortness of breath than mean values of individuals for these complaints in the sites of the study area. However there were more individuals in sites close to the mine and smelter/concentrator plant who experienced general body weakness, desire to spit often and shortness of breath than those at the control site. On the other hand, mean values of individuals in the study area who complained of all the other illnesses and diseases were higher than those at the control site (Table 5). Values for workers of suffering from frequent chest pains, repeated coughing, constant influenza/common cold and persistent headaches were significantly higher than those for workers at the control site in the order of persistent headaches > constant influenza/common cold > repeated coughing > frequent chest pains (Table 5).

Most common causes of chest pains include angina at rest and heart attack, although other causes are occlusion, pulmonary embolism and pneumothorax (Bahr, 2000; Erhardt et al., 2002; Husser et al., 2006). A high percentage of those who experienced chest pains also indicated suffering from frequent bouts of persistent coughing which was also attributed to fumes from the mine and smelter/concentrator, dust, weather and smoking of cigarettes (Ekosse et al., 2006c). Influenza /common cold could have been promoted by several factors including those associated with air pollution (Bruce et al., 1998; Cairncross, 2003; Loeb, 2003). There are different types and causes of headaches (Lipton et al., 2001; Olesen and Steiner, 2004; Voice of America, 2003).

| Table 5: | Mean percentages of respondents suffering from ailments, illnesses and diseases compared to the control site |

| |

Types include primary, secondary, or neuralgias and other headaches (Stovner et al., 2006; WHO, 2004). Causes could also be associated to allergies, sinus headache, low blood sugar, low stomach acid, as well as cluster headaches, tension headaches, migraine, vascular and hormonal headaches.

Chest pains have been related to breathing of gaseous fumes. The PAM including gases, such as SO2 and to a lesser extent H2S have a choking effect on human beings, affecting their respiratory system and causing them to have chest pains (Dominici et al., 2006). Persistent coughing experienced by workers was probably provoked by environmental conditions such as gases from mining and smelting activities and climatic factors like changing of seasons. During winter season, it becomes very dry and windy in Selebi Phikwe, causing a large number of dust particles to be suspended in the air for longer periods; causing those exposed outdoor of such environments inhaling PAM and eventually suffering from respiratory tract illnesses and diseases (Pope et al., 1995, 1999a). Environmental factors such as air pollution from industrial activities, climate and tobacco smoke can cause nasal congestion thereby triggering headaches (Aamodt et al., 2006; Schürks et al., 2006). Other factors suspected to be responsible for headaches at the study area are caffeine and alcohol consumption (Curry and Green, 2007) as depicted in a related study (Ekosse et al., 2006c). Very fine sulphur rich and heavy metals rich PAM due to mining activities (Ekosse et al., 2003) is frequently inhaled by the residents of Selebi Phikwe causing irritation to the respiratory pathway and could affect their respiratory tracts; thereby leading to a higher susceptibility to infectious diseases of the airways. Pope et al. (2004) demonstrated that there is a positive association of PAM with influenza. Nasal congestion, high body temperature of up to 39°C, chills, malaise, aching muscles, dryness in the mouth and throat, headache and shortness of breath are among the ailments resulting from inhaling copper fumes. On informally questioning inhabitants at Selebi Phikwe, they were of the opinion that the frequent chest pains, repeated coughing, constant influenza/common cold and persistent headaches could possibly be provoked by the mining and smelting activities; the main factors being dust, fumes and gases; among other indicators.

Table 5 links causes of ailments, illnesses and diseases to environmental factors due to mining and smelting activities, where applicable. It may not be very clear which of these illnesses and diseases affecting workers in the area are a direct result of the mining activities. However, illnesses and diseases such as frequent chest pains, repeated coughing, constipation, diarrhoea, constant influenza/common colds, persistent headaches, recent loss of body weight, lower abdominal pain, palpitations and pain when urinating could be a result of environmental air pollution or ingestion of contaminated Imbrasia belina (which feed on heavy metal contaminated Colophospermum mopane). These general health complaints have been identified as symptoms of reported illnesses and diseases in workers of enterprises in the Selebi Phikwe area. The illnesses and diseases include cancer, cardiac arrest, diabetes, pneumonia, tuberculosis, AIDS, stroke, meningitis, lung diseases and malaria. Irritation of the respiratory tract can lead to asthma, emphysema and chronic bronchitis and in fact, many people develop two or three of these together thereby leading to the constellation known as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (American Thoracic Society et al., 2003). Unexpected general body weakness which is not associated with physical effort such as dieting or exercises, sudden and significant loss of body weight and frequent nausea and vomiting have been attributed to AIDS and AIDS-related diseases, tuberculosis and cancer (American Thoracic Society et al., 2003). These three diseases (AIDS and AIDS-related diseases, tuberculosis and cancer) may be caused by several bacterial and viral agents, not necessarily associated with mining activities at Selebi Phikwe. Cancer has however been documented on deceased workers of nickel mining, smelting and refining industries (Roberts et al., 1989).

Health complaints of workers indicating persistent chest pains, frequent experiences of shortness of breath, asthmatic attacks, regular coughing and several occurrences of influenza/common colds could be symptoms associated with respiratory tract diseases that could ultimately lead to COPD or even lung cancer (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, 2003). Frequent and persistent headaches, influenza/common colds and acute chest pains have been diagnosed as precursors of meningitis, malaria and stroke. At Selebi Phikwe workers complained of these symptoms and deaths were reported of workers as a result of meningitis, malaria, cardiac arrest, diabetes and stroke. While there may be several causes of these diseases, at Selebi Phikwe PAM and gaseous fumes could be contributory.

The general health complaints, which also included AIDS-related issues and asthma made workers to be frequently admitted into health facilities. Absences of workers therefore increase and productivity was directly affected. Pope et al. (1995, 1999b) observed that there were increased hospital admissions because of respiratory problems and increased emergency room visits to hospitals due to respiratory problems caused by pollution emanating from PAM, SO2 and toxic fumes. Health complaints reported were increased lower respiratory tract symptoms and coughing, significant decrease in lung function and increased number of days of work or school missed. Although these observations by Pope et al. (1995, 1999a, b) cannot be presently substantiated from this study, the high percentage of workers who complained of persistent coughing could be attributed to the presence of pollutants resulting from the mining and smelting activities.

Because occupational health standards of workers and workplaces vary substantially according to economic structure, level of industrialisation, development status, climatic conditions and traditions of occupational health and safety (McGill University, 2003), It may be necessary for enterprises at Selebi Phikwe to identify the different mechanical, physical, chemical and biological factors affecting the health of their workers. Other factors that are crucial in determining environmental health hazards of contaminant metals include concentration of the contaminant, duration of exposure, how exposure happened and personal sensitivities due to age, gender, state of nutrition and general health (Moodie, 2001). These factors among others will enable the appropriate control measures to be put in place for implementation. In further reducing the influence of environmental health associated with Ni-Cu mining activities related to workers, as much as possible the labour force should avoid staying outdoors where risk exposure to contaminants is quite high; safety/protective gear should be used at all times when performing daily tasks; regular medical visits to monitor human health including checking of the cardio-pulmonary system, the circulatory system and urine should be carried out and occupational exposure programmes and environmental control measures should be frequently performed. Workers considered to be frail in health should seek employment and relocation other township area away from the influence of the emanating mining contaminants. Occupational safety and health policies, programmes and procedures should be put in place and/or enforced. These measures and other related health monitoring programmes would definitely ensure quality lifestyle for sustainable development applicable to the workers at Selebi Phikwe.

Although the illnesses and diseases mentioned may have been contributory causes of reported deaths of workers, not all cases of mortality could be associated with mining activities. Only cases of lung diseases, pneumonia and some cancers which could have been provoked by PAM, gaseous fumes and heavy metals, could be tied to possible partial causes of some of the deaths which have occurred in the Selebi Phikwe area as a result of mining activities. Sulphur dioxide emitted from the roasting of the ore, PAM, tailings dump, contaminated soils, contaminated Colophospermum mopane and Imbrasia belina were identified in previous studies by Chimidza and Moloi (2000), Ekosse et al. (2005) and Ekosse et al. (2003, 2004) to be sources of contamination and these contaminants could possibly be affecting the health of workers living within the Selebi Phikwe area.

CONCLUSION

This study investigated the health status of workers of business enterprises within a Ni-Cu mine and smelter/concentrator plant area in Botswana through the administration of questionnaires. Results depicted that workers suffered from the following major symptoms and illnesses in Percentages: persistent headaches 70, frequent influenza/common colds 66, repeated coughing 45, body weakness 42 and constant chest pain 40. Workers in sites closer to the Ni-Cu mine and smelter/concentrator plant area were the most affected by the symptoms and diseases. In terms of business type, workers engaged in mining and agricultural activities suffered the most compared to those in other types of businesses.

Research findings of this study inferred that the mining and smelting activities could be contributory to chest pains, repeated coughing, influenza/common cold and headaches which workers of the environment suffer from. Deaths have also been reported with the highest occurrences registered in the most industrialised part of the study area. Cases of deaths of workers occurred in all the study sites except sites five, eight and nine. Most of the deceased were between the ages of 21-45 years old and slightly more females workers were reported to have died compared to male workers. A wide range of diseases including cardio-pulmonary complications were the immediate causes of deaths. Several environmental factors due to disturbances of the biophysical environment as a result of mining activities have affected the health status of the workers of area. These findings are in conformity with those of previous related studies and could inferably be applicable to other similar Ni-Cu mining environments around the world.