Research Article

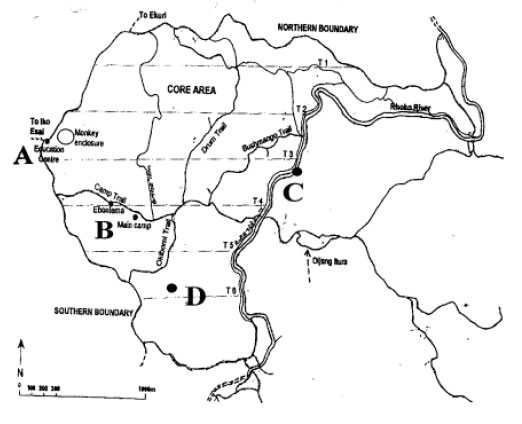

Prevalence and Seasonal Distribution of Daytime Biting Diptera in Rhoko Forest in Akamkpa, Cross River State, Nigeria

Department of Zoology and Environmental Biology, University of Calabar, P.M.B. 1115, Calabar, Nigeria

Donald A. Ukeh

Department of Crop Science, University of Calabar, P.M.B. 1115, Calabar, Nigeria

Nsa E. Dada

Department of Zoology and Environmental Biology, University of Calabar, P.M.B. 1115, Calabar, Nigeria