Research Article

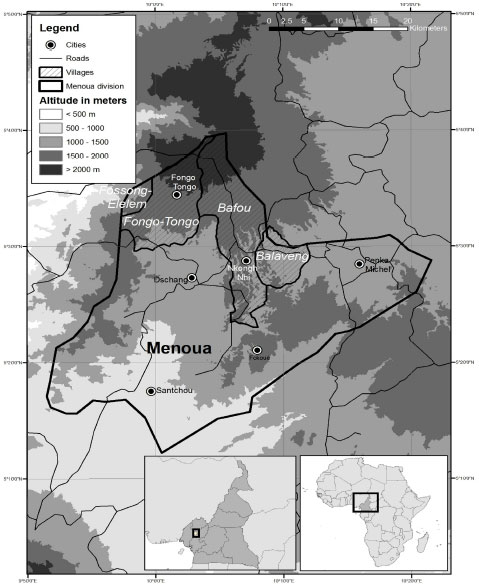

Soil Quality Assessment of Cropping Systems in the Western Highlands of Cameroon

Faculty of Agronomy and Agricultural Sciences, University of Dschang, P.O. Box 222, Dschang, Cameroon

G.R. de Snoo

Institute of Environmental Sciences, Leiden University, P.O. Box 9518, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands

H.H. de Iongh

Institute of Environmental Sciences, Leiden University, P.O. Box 9518, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands

G. Persoon

Department of Anthropology, Leiden University, P.O. Box 9518, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands