Research Article

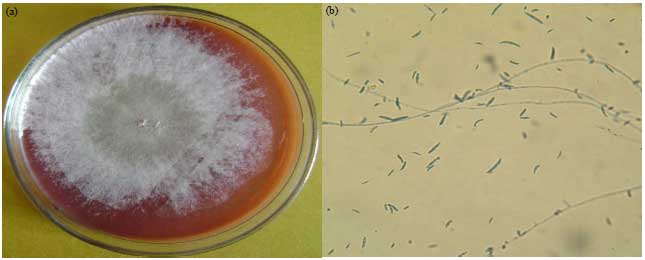

Occurrence and Prevalence of Mycotoxigenic Fusarium solani in Onion Samples Collected from Different Regions of Libya

Center for Global Programs (CGP), Management and Science University (MSU), Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

Mohammed Abdelfatah Alhoot

International Medical School (IMS), Management and Science University (MSU), University Drive, Off Persiaran Olahraga, Seksyen 13, Shah Alam, 40100, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

LiveDNA: 970.24768

Kartikeya Tiwari

International Medical School (IMS), Management and Science University (MSU), University Drive, Off Persiaran Olahraga, Seksyen 13, Shah Alam, 40100, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

LiveDNA: 60.15110